David Alward, Premier of New Brunswick

Centennial Building

P.O. Box 6000

Fredericton, NB E3B 5H1

Dear Premier Alward:

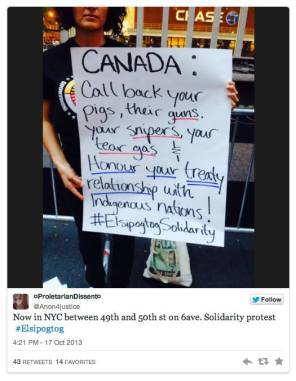

Our organizations are deeply concerned by the Province of New Brunswick’s response

to anti-fracking protests at the Elsipogtog Mi’kmaq Nation. We are appreciative of

the efforts of all involved to allow a cooling off period following the violence of

October 17. However, it is our view that this clash could have been avoided had the

province acted in a manner consistent with its obligations to respect the human rights

of Indigenous peoples under Canadian and international law. Furthermore, we are

concerned that unless the province adopts an approach consistent with these obligations,

further clashes may occur.

In 2007, an Ontario public inquiry into police and government response to Aboriginal

protest – the Ipperwash Inquiry – concluded that blockades and occupations are

“symptoms” of the long-standing failure of governments in Canada to resolve land

and resource disputes in a fair, timely and effective manner. In the Inquiry report,

Justice Sidney Linden wrote that blockades and occupations “occur when members

of an Aboriginal community believe that governments are not respecting their treaty or

Aboriginal rights, and that effective redress through political or legal means is not

available.” Justice Linden called for a redoubling of efforts “to build successful,

peaceful relations with Aboriginal peoples…so that we can all live together peacefully

and productively.”

In this spirit, our organizations highlight four areas where we believe the province of

New Brunswick can do more to rebuild just relations with Indigenous Peoples in

relation to resource development and the potential for disputes.

First, it is critical to acknowledge that Indigenous Peoples have rights to their lands, territories and resources that predate the creation of the Canadian state. These pre-existing rights are affirmed in the Peace and Friendship Treaties, in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, and in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, as well as in authoritative international human rights instruments including the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Canada’s failure to protect these rights has been repeatedly condemned by international human rights bodies, including the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which found that the comprehensive claims processes fall below international standards of justice. Your government can make a meaningful contribution by communicating clearly that these rights exist and must be respected.

Second, the inherent land rights of Aboriginal peoples cannot be ignored in the day-to-day operations of the government. Doing so is both discriminatory and contrary to the rule of law. Canadian courts have set out a mandatory constitutional duty to consult with Indigenous peoples with the goal of identifying and substantially accommodating their concerns, before any decisions are made that could affect these rights. For such consultation to be meaningful, Indigenous peoples’ knowledge and perspective must be part of the determination of whether or not a particular proposal could have a harmful impact on their rights and use of the land. Furthermore, the duty of consultation and accommodation, and the inter-related obligation for governments to deal honourably with Aboriginal peoples, cannot be met if there is a predetermination that projects will go ahead regardless of legitimate concerns raised by the affected communities. Accordingly, our organizations urge your government to retract statements indicating that the province is already committed to shale gas development, regardless of opposition.

Third, whenever a proposed project has the potential for impacts on the cultures, livelihoods, health and well-being of Indigenous peoples, or where questions remain about the extent of the possible impacts, a very high standard of precaution is required to ensure that no further harm is inflicted on Indigenous peoples. Canadian courts have said that the “full consent” of Aboriginal peoples may be required on “very serious” matters. International human rights instruments, and the jurisprudence of international human rights bodies, clearly establish a duty to obtain the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of Indigenous peoples as a precautionary measure or heightened safeguard for their rights. In fact, just days before violence erupted over the shale oil explorations in New Brunswick, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples reminded governments in Canada that FPIC is generally required whenever large scale resource development projects are being considered that could impact the rights of Indigenous peoples. Our organizations call on New Brunswick to acknowledge that shale gas exploration and development on or near the traditional lands of Indigenous peoples is clearly an example where the safeguard of free, prior and informed consent is appropriate and necessary.

Finally, our organizations highlight the need to ensure appropriate police response in the unresolved conflicts over Indigenous lands rights. In all instances, police have a clear responsibility to respect and protect human rights. While police have an obligation to protect public safety and respond to criminal offences, police must also act to respect the right of peaceful protest and assembly and act to protect the lives and safety of those involved in protests. Use of force must always be a last resort and the scale and nature of the force deployed must be in proportion to the need to protect public safety. In the Ipperwash Inquiry report, Justice Linden called on Ontario to adopt a province-wide peacekeeping policy based on these principles to ensure that police response to Aboriginal protest would not be politicized and that risks of violence could be minimized. Our organizations strongly urge all governments in Canada to also publicly endorse and adopt such crucial policies.

Yours sincerely,